Thoughts from my Faculty Application Experience

Ben Lengerich

- Application cycle: Fall 2023- Spring 2024

- General background: PhD in CS @ CMU, Postdoc @ MIT CSAIL

- Applications to departments of Statistics, CS, and Biomedical Informatics

- Accepted position at University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Statistics

- List of useful resources at the end

0. Who I am

My name is Ben Lengerich. I’m an incoming assistant professor in the Department of Statistics at UW-Madison, starting Fall 2024. I come to this appointment by way of training in CS, with a research focus on ML for healthcare. In reverse chronological order, I was a postdoc at MIT CSAIL, a PhD student at CMU CS, and an undergrad at Penn State. You can read more about my research interests on my group website here.

I was on the faculty market in the 2023–2024 application cycle, and this is my story. I am writing this in the hope it will help others in their academic journeys. I applied to positions in Statistics, CS, and Biomedical Informatics, so this writeup will be most applicable to people with a similar area of interest in ML for healthcare.

This writeup is intentionally not exhaustive. I’ve prioritized including thoughts here that I haven’t seen discussed elsewhere, and I’ve cut out as much redundancy as feasible. With this attempt at brevity, this writeup is certainly no more than an n=1 experience. To give a broader view of the process, I’ve included a list of resources at the end of this writeup.

1. The General Outline of Faculty Job Searches

The faculty job search is a long process. It typically involves an electronic application, a remote interview, a 1–2 day in-person seminar/interview, a potential second visit, and negotiations. The flow of my own applications is shown below. I submitted 89 applications, and the most common response to these applications was silence.

Timeline

The general timeline has applications in the fall (with deadlines clustered around November-December), remote interviews in the winter, and in-person interviews throughout the spring. Including time to prepare applications and finalize an offer with negotiations / second-visits in late spring, it’s quite possible for the faculty job search to be the highest priority project for the better part of an academic year.

Within this general framework, specific deadlines vary considerably. I tracked my applications on a spreadsheet and recorded the date (if any) listed in the job description as a deadline, the date (if any) listed as the time when the search committee would “begin consideration”, and my own application times. For both “deadline” and “begin consideration”, the most common date was December 1. The dates ranged from June to January. Some schools used a rolling application process, which I found more difficult to understand the logistics and set expectations. Medical schools tended to schedule earlier than other departments. I believe that is because the academic year often starts in July for medical schools, rather than the August/September start date more typical of other departments.

I also recorded my interview dates. Most remote interviews happened in January, and most seminars/in-person interviews happened Feb-Mar.

Competition / Rankings

Faculty jobs are competitive. Two schools shared some stats in their rejection emails to soften the blow of rejection. For a single tenure-track position in CS, one school reported >700 applications and the other reported >400 applications. The first school was “ranked” in the top 35 in the US for CS, and the second in the top 75. I expect the application counts would rise even further when climbing the “ranking” ladder.

I use “ranking” in quotes because there is no perfect ordering of schools or applicants. For example, in the anecdote above, I was rejected from two CS departments “ranked” around #35 or #75, while I received offers from a few “ranked” in the top 20. Desirability of both school and applicants are far from universal, so any attempt to provide universal “rankings” will include some bias (I appreciate this attempt at debiasing rankings by simultaneously viewing multiple ranking methodologies). I would advise keeping one’s mind open to a wide variety of schools, and not stressing about being the “best” candidate, but rather just to be the best version of yourself.

Soft / Hard Money

I will use the terms soft/hard money throughout to describe some of the differences in applications for different positions. Hard money is guaranteed by the institution and is in exchange for services to the institution (e.g. teaching). Soft money is a salary rate at which you can be funded by external sources (e.g. federal grants), but the funds are not guaranteed by the institution. Positions can range from 0% hard money (=100% soft money) to 100% hard money (=0% soft money). Most CS and Statistics positions are 100% hard money because they have a large number of undergraduate (i.e. paying) students. Most research positions in medical schools include soft money because they have reduced teaching expectations. Since a soft-money salary is drawn from external funding and new assistant professors need time to get external funding, startup amounts at positions with soft money tended to be higher than startup amounts at positions with hard money.

2. The Application

Applications consisted of a cover letter, a CV, 2–3 essays (research statement, teaching statement, and a diversity statement), 3–5 reference letters, and potentially 1–3 writing samples. You can find my Latex templates here.

I recommend MIT’s resources for writing a good application. One interesting recommendation contained therein is to write a branding statement prior to writing any individual components. I found this to be a useful exercise. It was difficult to compress a research vision into an elevator pitch, and even more difficult to compress my entire application package into a phrase/word, but I found this exercise useful for organizing my thoughts and ensuring cohesion. My keyword was “context”.

3. The Applying

I chose to apply broadly, seeing potential homes for myself in departments of Statistics, CS, and medical schools. I ended up receiving offers from at least one department of each type, so I think this strategy aligned well with my opportunities.

To apply broadly, one can either spend lots of time tailoring applications to departments, or reuse the same basic application package and do only minimal edits for each department. I chose to reuse the same basic application package (rewriting the cover letter only). While this helped for practical purposes of saving time, I chose this strategy for a different reason: I wanted to write an application package I really meant and then let the schools decide if they saw a fit in me, rather than attempting to tailor myself to my impression of a school’s desires. There are good arguments both ways on this topic.

Finding jobs

For CS, many jobs are posted on CRA and AcademicJobsOnline. I would recommend subscribing to email updates during your job search. I also subscribed to job posts on Science.

Tracking applications

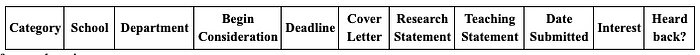

I made a spreadsheet of departments with the following columns:

A few explanations:

- Category: One of [Expecting Posting / Job Posted / Applied / Interview Scheduled]. Once per month, I checked the websites of all the departments for which I was “expecting posting”.

- Cover letter / research statement / teaching statement: Schools had slightly different formatting requirements for their applications, so I needed to track which format would need to be made / used for that application. I made a new cover letter for each school, and these needed to be written for each school.

- Interest: I forced myself to quantify my interest level for each department so I could allocate more time to more interesting opportunities. These changed as I learned more about the departments

Most jobs had submission on Interfolio. Unfortunately, Interfolio didn’t have a good way to discover relevant postings. However, it could remember my materials across applications, enabling me to re-use pieces of the application when formatting was consistent. Some posts were on AcademicJobsOnline, which did have a discovery page, but I found fewer jobs requesting submission there than on Interfolio.

Letters

I used Interfolio to handle my materials. This was especially useful for letters of recommendation, because letter writers needed to upload their letter just once to Interfolio instead of uploading a letter to each application separately. For any application hosted on Interfolio, I could directly attach the letters previously uploaded to Interfolio, while still maintaining confidentiality. For applications hosted elsewhere, there was a mechanism where I could submit an Interfolio-generated email address, and when that email address received a request for a letter, Interfolio would respond with the confidential letter. This greatly streamlined the process of organizing letters.

It also gave me a surprising benefit of being able to track a few applications. Since Interfolio would notify me when a delivery of letters was made, I could find out when schools were looking at my application. Most schools would request letters as soon as I submitted the application, so it wasn’t terribly informative, but for a few schools, they only requested letters after a month or two. This was interesting for me to follow.

Deadlines

Many job postings listed two deadlines: the date when all applications should be received (I will call this “deadline”) and the date the faculty will begin reviewing applications (“begin consideration”). Did submitting before these dates actually matter? Below are the results of my applications, stratified by how early I submitted the application. I call an application “successful” if it led to an interview, and “unsuccessful” otherwise. My applications that were submitted earlier had higher success rates.

4. Remote / Screening Interviews

Most invitations to a remote interview included a description of the procedure and a list of participants. This was critical information because the timing was short and the opportunity to make a first impression fleeting. If any information is missing, I would recommend asking for further details when accepting the invitation.

The most common pattern was a 30 minute Zoom meeting, with directed questions including:

- Research successes

- Research vision

- Teaching experience, philosophy, and specific courses to teach

- Views on and initiatives to expand diversity in the field

- Specific collaborations at the university

If the position includes soft money, they also asked about funding plans.

I didn’t find that these interviews had much back-and-forth, but were instead more of directed question-and-answer. Being prepared with my answers was important because there wasn’t much of a conversation to tie them together.

Some places suggested I show a small number of slides during the conversation. I found this helpful as an exercise to focus my vision.

Environment

It’s important to have an environment for a professional image. I invested in a Blue Yeti mic, a pop filter, a desk light, and headphones. It may be good to get an external webcam, but I used the one on my Mac.

Your Questions

Remote interviews typically included 5 minutes for me to ask questions. I received contradictory advice regarding which questions to ask at this stage — for example, some people told me to ask about tenure requirements in order to understand the values and success metrics, while other people told me it would be presumptive and borderline offensive to ask about tenure requirements while on a remote interview. I decided to try to think from my perspective if any information would make the difference between accepting/rejecting an invitation for an in-person visit.

The “one-month” rule of thumb

After the interview, some institutions reached out with an invitation for an in-person interview, some reached out with a rejection, and some did not send me any updates. I found that a “one-month” rule of thumb tended to be fairly reliable — if no updates for one month, then I would likely not be moving on to the next round. While some processes were slow and took longer than a month, once a month had passed, I found it better to mentally prepare to be rejected.

5. In-person Interviews and Seminars

An in-person interview typically included a research seminar, one-on-one meetings with faculty members, and meetings with graduate students. Positions that involved soft money often included a “chalk talk” as well.

Host

Since in-person interviews involved travel to a potentially unfamiliar location, most institutions paired me with a “host” for the day. This was quite nice: the “host” was often picked because they have research interests closely aligned with mine, and their job was to be a friendly face to me. In addition, the host was typically hoping I would get hired, both because they believed in my research area (it helped they had a similar research vision) and because they believed we could accelerate each other’s research via collaborations.

Beyond my host, I found that the people in my area were also largely in favor of my hiring, for much of the same reasons. This was likely the pleasant outcome of a selection bias: when the faculty in my area didn’t want to hire me, they didn’t invite me to an in-person interview. The more lukewarm and undecided faculty members were those with research interests outside of my area, who couldn’t easily evaluate my research and thus needed some explanation before they could make an informed evaluation.

However, to get hired, both groups of faculty must be in favor. Seen this way, the goal of the in-person interview was to turn the potential collaborators into enthusiastic advocates and the rest of the department into supporters.

Research seminar

The research seminar was enjoyable — I got to give an invited talk about a subject that I found fascinating. Amazingly, faculty tended to pay very good attention to the research seminar and asked very good questions. This may be the only time in my career that faculty outside of my area make an active effort to understand my work and creatively find potential collaborations. I found this quite enjoyable. It was also enjoyable to put together my seminar and think about how my research vision coalesced into an exciting story.

Different departments had different cultures regarding the research seminar. I found that CS departments tend to like flashy, comprehensive presentations that included the speaker’s main hits and impressed with the breadth of excellent material. Statistics departments tend to like deep dives into a smaller number of problems with technical details highlighted. Medical schools tended to like actionable problems with clear benefits to clinical care.

I came to imagine the research seminar as a walk in a forest where there are dark, winding paths but a hidden treasure in the middle. My job was to take the audience to this forest, show them the hidden treasure, and guide them out of the forest. Different audience members would have different takeaways. Some audience members (those outside my field) didn’t know the forest existed, and my job was to show them that the treasures in the center of the forest are so wonderful that they want to be colleagues with someone working in the middle of the forest. Some audience members (those in my field working on different problems) were waiting on the edge of the forest; they needed the cool nuggets and takeaways to be enticed to wander in. Some audience members (those working on the same problems) were interested in the trail markers and technical details. Having all these audience members and their needs in mind was key. Practically speaking, the most important might have been the more distal audience members — they needed to be convinced that my area is really exciting, while the nearby audience members must have already been interested and impressed (else they wouldn’t have invited me).

Chalk talk

A chalk talk is an interactive description of your research vision and funding plans (sometimes described as “draw your first R01”). I found this video useful for preparation. I found chalk talks to be more common in positions with soft money than in positions with 100% hard money.

One-on-ones

During visits, the most common meetings were one-on-ones with a faculty member. One-on-ones were the most exhausting and the most exciting part of the interview process. Most of these were 30 minutes long, and there were up to 15 in a day.

The exhaustion had an upside, though: I got to meet people. Altogether, I got to meet >200 faculty members. I learned about all sorts of areas of research and potential collaborations, and I now have personal contacts with friendly people across many great departments. It was an amazing introduction to the field.

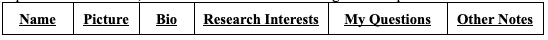

To prepare for one-on-ones, I made a table with the following columns prior to each visit:

Most one-on-ones had some back-and-forth conversation, with questions from the faculty and time at the end for the applicant to ask questions. I found a good source of potential questions was Interview Questions for Computer Science Faculty Jobs.

For my own questions, I had some that were tailored to individual faculty members. For others, I used more generic questions, including:

- Senior faculty — How has the department changed? Department strengths and weaknesses? What type of faculty are most successful here? What’s something that impacts your quality-of-life that wasn’t obvious from a non-faculty viewpoint?

- Junior faculty — What brought you here? How have you gone about setting up a group and recruiting students? Advice for the first few years? Surprises/mistakes in your first few years? What is the mentorship process?

I found the meetings most enjoyable when the person was very honest (e.g. willing to tell me tradeoffs of the school) or had a research overlap that we could think about collaborations. Research is fun, and unexpected connections are fun, so I’d recommend working hard to find an overlapping area of research during your one-on-one.

Tip: The schedule may not include bathroom breaks. However, nobody is tracking how frequently you go to the bathroom, and everyone will excuse you for five minutes to go to the bathroom before your meeting. You can also ask to go even if you just need to look at your prep sheet.

Student meetings

I don’t have many insightful comments to make about student meetings. I felt that I couldn’t prepare for them individually because the department typically didn’t know which students would attend. Some students wanted advice for their careers, some students wanted to judge me and pass their feedback to the hiring committee, and some students wanted to have technical discussions to help them on a project they are stuck on.

Dinner

Shared meals, potentially including breakfast, lunch, and dinner, were common. These were of course interviews, but more conversational than other one-on-ones. I found it good to order a dish that was easy to eat so that I could focus on the conversation rather than my own utensils. My go-to was a salmon filet.

International Interviews

I interviewed at one institution in continental Europe. From this sample size of n=1, there were many differences from US interviews, so I would recommend researching the common practices of any new locations and asking for clarification for anything that is the slightest bit confusing. At my interview, there was something called an “interview” with the hiring committee that ended up being a chalk talk. This was an embarrassing situation and one I could have avoided by asking more questions prior to visiting.

Travel

Each in-person interview included travel (likely a plane ride), a seminar day, and potentially a second day of one-on-ones. I found the travel exhausting and could only manage to do 1 good in-person interview per week. I eventually had to schedule 2/week, but got very tired and quite sick. Take care of yourself.

Costs and Reimbursement

Schools should pay for your travel, but the logistics can be a little complicated. I found that most schools booked the hotel directly and reimbursed me for flights/miscellaneous expenses. The reimbursement can take a while, up to a month. I made a spreadsheet to track reimbursements.

6. The waiting

After an in-person interview, there was a new period of waiting. I found my support system (family, especially) very helpful.

Just like after the remote interviews, I found the one-month rule-of-thumb useful, but needed a slight extension in this case: none of the schools moved to an offer within a month of my in-person visit, though they were very close. A nice difference between the waiting after an in-person interview and the original application is that this time I had personal contacts with the department, so I could reach out for status updates.

7. Second visit / Negotiations

After an offer comes negotiations. You may also be invited for a second visit, and this second visit may be before or after receiving the official offer. For personal reasons, I didn’t do any second visits.

Items to negotiate include:

- Startup

- Salary*

- Teaching releases

- Compute resources

- Personnel support

- Equipment

It’s possible to hire a negotiation coach to help you. I didn’t do this, but I did watch several videos about academic negotiations. I found the following useful:

- Faculty Job Search Prep Camp — Negotiating for Faculty Jobs

- Negotiating your first academic job offer

- You Got the Job, Now What: Negotiating!

- Negotiation strategies on the academic job market

Once I had received a few offers from departments I liked, I withdrew my applications from any schools where I knew I wouldn’t be accepting an offer. This was difficult because I genuinely liked the other schools. Nevertheless, I felt I should be as forthright as possible, and let them know as soon as I had made a decision. Department chairs typically wanted to know where I was going and if there was anything they could do to improve the appeal of their department.

I then began negotiating with a couple schools. I made a detailed budget of the expected costs of my research group for my first three years, and told the schools what I thought it would take for me to be successful at their institution. They tended to respond by first verifying that I had exhausted the resources at the school before allocating money toward my version of those resources. For example, the University of Wisconsin has the excellent Center for High-Throughput Computing; it’s better to allocate some of those resources to my group rather than purchasing my own GPUs. Shared resources can be great.

In my experience, the most effective negotiating strategy was to ask to match an offer from a competing school. This is because of how resources are allocated in academia. If department resources are exhausted, they may still be able to offer college or university resources. This means that if the department is out of resources, your job in negotiating shifts from convincing the department head that you are worth the money to equipping the department head to make an appeal to administrators for more resources. As the dean/provost/etc are less familiar with the research area of the prospective hire than is the department head, appeals to technical requirements will be less persuasive to the dean and provost than to the department head. Instead, appeals to matching direct competitors seemed to be the most impactful.

*When thinking about salary at a hard money position, it’s important to understand 9-month salaries and summer support. Most salaries are quoted as compensation for 9-months of work (though paid over the full year), with the potential of additional salary for work in the summer (paid via summer teaching or soft money).

8. Onward!

Now we get to be (assistant) professors! Let’s do good work, serve our students, and serve the community.

If you found this guide useful, feel free to drop me a note.

Other Resources

- This writeup was inspired by Daniel Seita’s writeup from 2023. I recommend reading his thoughts, and he compiled a great list of resources.

CS Academia:

- Academic Job Search

- Interview Questions for Computer Science Faculty Jobs

- https://sites.google.com/view/elizabethbondi/blog?pli=1

- Guide to Professorspeak

Faculty jobs more broadly:

- Faculty Application : EECS Communication Lab

- https://rosecersonsky.com/assets/slides/2022-06-14-academic-jobs.pdf

- Workshop on Faculty Hiring Process — YouTube

- Tips for negotiating salary and startup for newly-hired tenure-track faculty | Dynamic Ecology

- Faculty job talks: tips from the faculty — MIT EECS

- Thoughts on applying for faculty jobs